Posted by Yugo Koshima, Jason Harris, Alexander F. Tieman, and Alessandro De Sanctis[1]

A recent IMF Working Paper on “the Cost of Future Policy: Intertemporal Public Sector Balance Sheet in the G7" delves into a new approach to assessing fiscal sustainability. Going beyond the standard view of deficits and debt, the working paper uses the Intertemporal Net Financial Worth (INFW) of the public sector as a key measure of fiscal sustainability (see the IMF’s October 2018 Fiscal Monitor for more details). INFW is computed as the net financial worth of the public sector (static) balance sheet, comprising all assets and liabilities controlled by the government (including state-owned enterprises), plus the net present value of future primary balances. The former represents consequences of past fiscal policy, while the latter shows the cost of future policy.

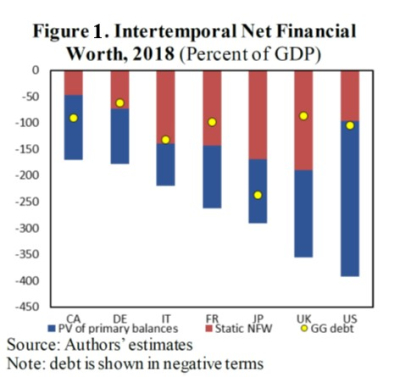

Our study presents a remarkable picture of INFW of G7 countries (Figure 1). The average INFW across the G7 was minus 267 percent of GDP in 2018, with none of the countries having sufficient fiscal resources to meet their spending promises under current policies. This picture likely worsened further during the COVID-19 pandemic. These shortfalls are driven by negative NFW at the outset (i.e., these countries currently already owe more than they own) and growing future health obligations in light of population aging. Closing the gaps would require adjustment of the primary balance by an average 7 percent of GDP.

The size of these adjustments varies across countries, with Japan requiring the largest adjustment (over 10 percent of GDP), and Canada the smallest (3.6 percent of GDP), depending mainly on varying interest rate and growth differentials across countries. It is important to note that negative INFW are not inevitable for advanced economies facing demographic pressures: similar assessments for Finland (Brede and Henn, 2019)[2] and Norway (Cabezon and Henn, 2019)[3] show positive intertemporal net financial worth.

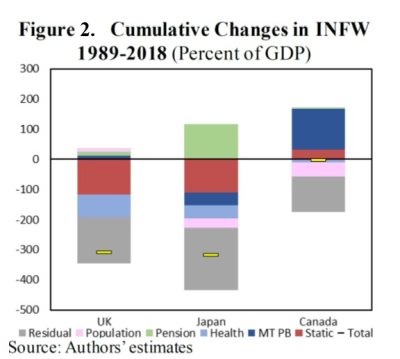

The Working Paper also offers a decomposition of the historical evolution of INFW in three countries. Over the past 30 years Japan and UK have recorded INFW deteriorations greater than 300 percent of GDP, while Canada’s INFW ended largely where it began (Figure 2). In all three countries INFW experienced large short-term fluctuations, mostly driven by fiscal policy changes, while demographic developments and associated health obligations contributed to a steady long-run deterioration.

The study also examines whether INFW strength is reflected in lower borrowing cost, i.e., is there a relationship between long-term interest rates on sovereign borrowing and the strength of a country’s intertemporal balance sheet? Regressions of slopes of future yield curves on INFW for Canada, UK and Japan find a modest but statistically significant relationship. On average, a 10-percentage point of GDP improvement in INFW reduces spreads between one-year and ten-year interest rates ten years ahead on government bonds by 2.8 basis points. This suggests that when INFW improves, the yield curve flattens, possibly because market participants take INFW into account when assessing a country’s sovereign credit risk. While challenges remain in the robustness of estimation given the limited sample size, this result suggests that financial markets may take account of governments’ long-term obligations and future revenue potential.

Further research on INFW could promote the application of the balance sheet approach to fiscal policy assessment. For example, it could assess the ways in which INFW has been influenced by the shock to public finances and growth from the COVID-19 pandemic. Expanding the analysis of INFW to more countries could generate firmer conclusions on the role of financial markets in signaling the long-run sustainability of public finances.

[1] Authors are from the IMF’s Fiscal Affairs Department except Alessandro De Sanctis, Paris School of Economics.

[2] Brede, Maren and Christian Henn, 2019, “Finland’s Public Sector Balance Sheet”, Baltic Journal of Economics, 19(1), pp.176-194.

[3] Cabezon, Ezequiel and Christian Henn, 2019, “Norway’s Public Sector Balance Sheet”, Applied Economics Letters, published online.

Note: The posts on the IMF PFM Blog should not be reported as representing the views of the IMF. The views expressed are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of the IMF or IMF policy.